Complete Mastery of vLLM: Optimization for EVA

In this article, we will explore how we optimized LLM service in EVA. We will walk through the adoption of vLLM to serve LLMs tailored for EVA, along with explanations of the core serving techniques.

1. Why Efficient GPU Resource Utilization is Necessary

Most people initially interact with cloud-based LLMs such as GPT / Gemini / Claude. They deliver the best performance available without worrying about model operations — you simply need a URL and an API key. But API usage incurs continuous cost and data must be transmitted externally, introducing security risks for personal or internal corporate data. When usage scales up, a natural question arises:

“Wouldn’t it be better to just deploy the model on our own servers…?”

There are many local LLMs available such as Alibaba’s Qwen and Meta’s LLaMA. As the open-source landscape expands, newer high-performance models are being released at a rapid pace, and the choices are diverse. However, applying them to real services introduces several challenges.

Running an LLM as-is results in very slow inference. This is due to the autoregressive nature of modern LLMs. There are optimizations like KV Cache and Paged Attention that dramatically reduce inference time. Several open-source serving engines implement these ideas — EVA uses vLLM. Each engine differs in model support and ease of use. Let’s explore why EVA chose vLLM.

2. Why vLLM?

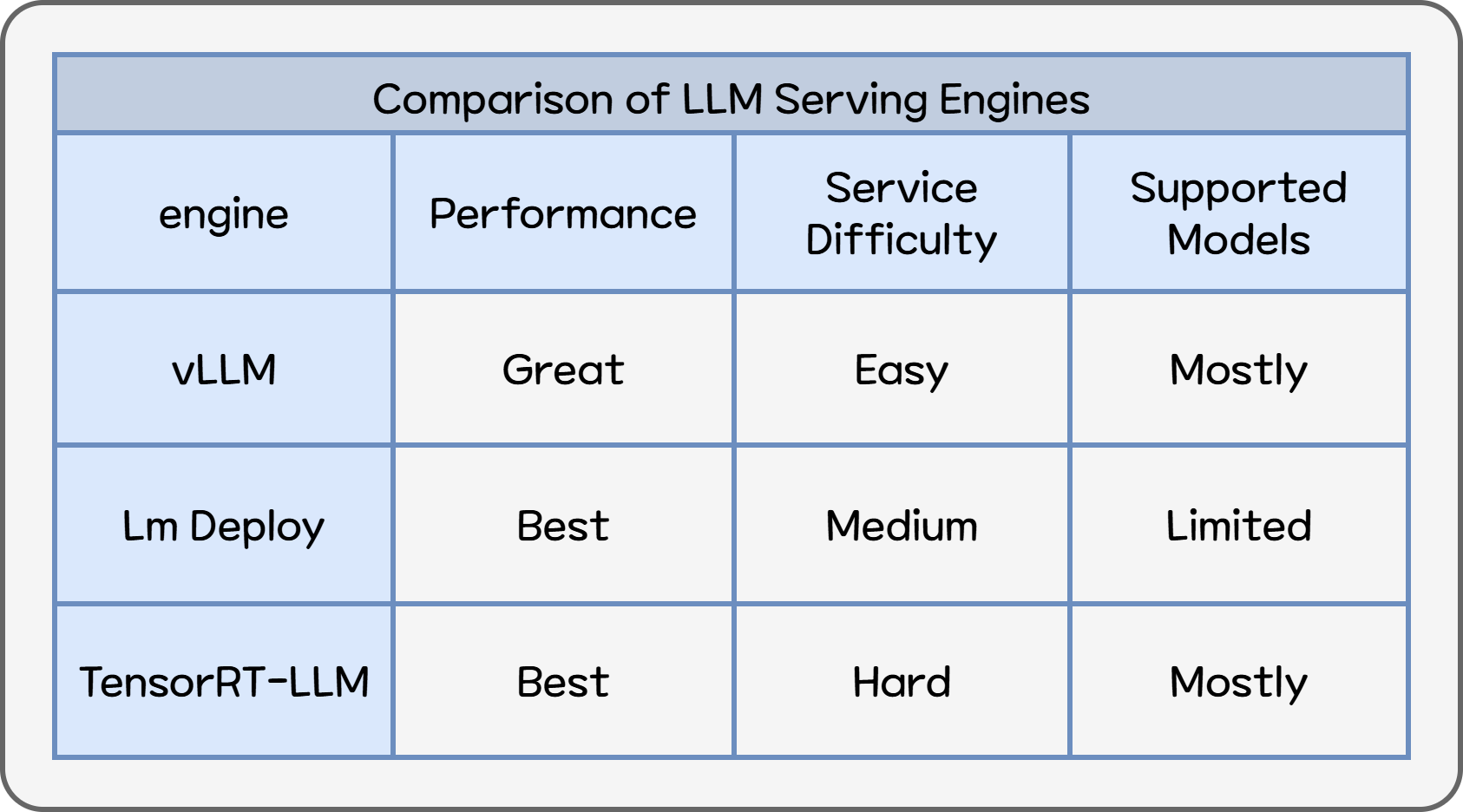

When evaluating LLM serving engines, we focused on three criteria:

- Supports many models

- Operates easily

- Provides reasonable performance for real services

Among many serving engines, we shortlisted vLLM, LM Deploy, and TensorRT-LLM, and ultimately selected vLLM. vLLM supports the largest variety of Hugging Face models and provides stable performance without model conversion. We also considered LM Deploy and TensorRT-LLM, which score higher in external benchmarks, but:

- LM Deploy supports fewer models

- TensorRT-LLM requires dedicated model conversion

When comparing serving engines, the main criteria are:

- Throughput

- TTFT (Time To First Token)

Throughput measures how many tokens/requests per second the GPU can generate — “how much the GPU worked within a second.”

TTFT (Time To First Token) is the time between sending a request and receiving the first token. This directly affects user-perceived latency — often the most important UX metric.

vLLM has a strong advantage in maintaining low TTFT. In a benchmark by BentoML using Llama 3 8B/70B under identical conditions:

- LM Deploy provided higher throughput

- vLLM kept the lowest TTFT under every load condition1

Other benchmarks also show:

EVA continuously updates its selection of cost-efficient open-source models. Among the three engines, vLLM supports the most LLM architectures, including Embedding models and Mamba4.

Finally, ease of operation matters:

- With vLLM, just change the HF repo name

- Other engines → conversion and extra operational burden

Table 1. LLM Serving Engine Performance Comparison

EVA must support diverse use cases with models optimized per scenario. vLLM may not always rank first in raw performance, but performance differences do not significantly impact service quality.

LM Deploy / TensorRT-LLM → highest peak performance but high operational cost vLLM → best balance of performance, compatibility, and manageability

3. Core Technologies for LLM Serving

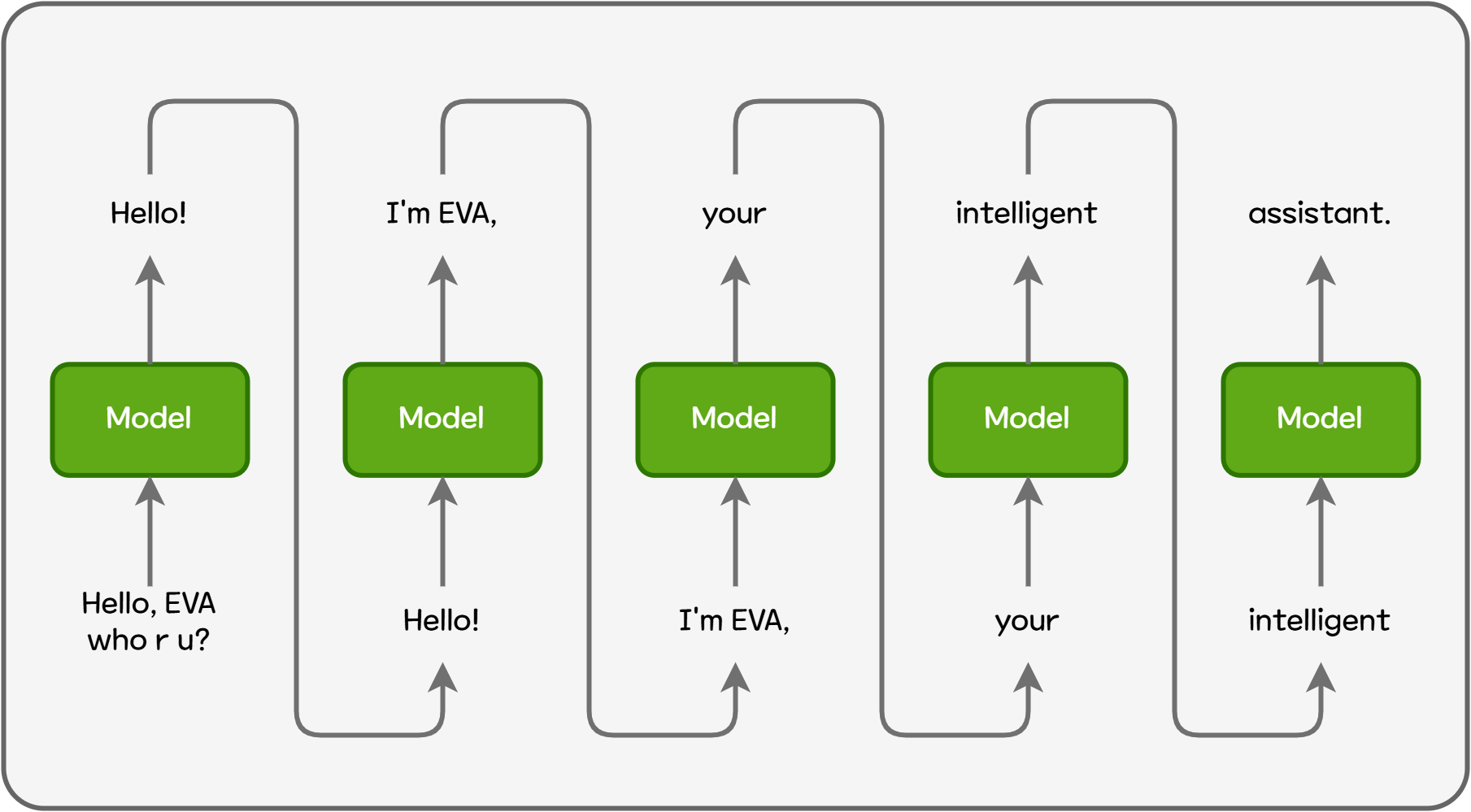

Now, let's take a look at the technologies that enable LLM serving engines like vLLM to achieve significantly better performance than plain LLM inference. LLMs are autoregressive models that generate the next output token by repeatedly feeding previous outputs back into the model. For example, when generating the sentence “Hello! I'm EVA, your intelligent assistant.”, the model cannot generate the whole sentence at once or generate each word in parallel. It must generate output sequentially at the token level.

Figure 1. Autoregressive Model Inference

Each time a token is generated, the model needs information from all previous tokens. For example, to generate the final token assistant, the model must revisit the four preceding tokens.

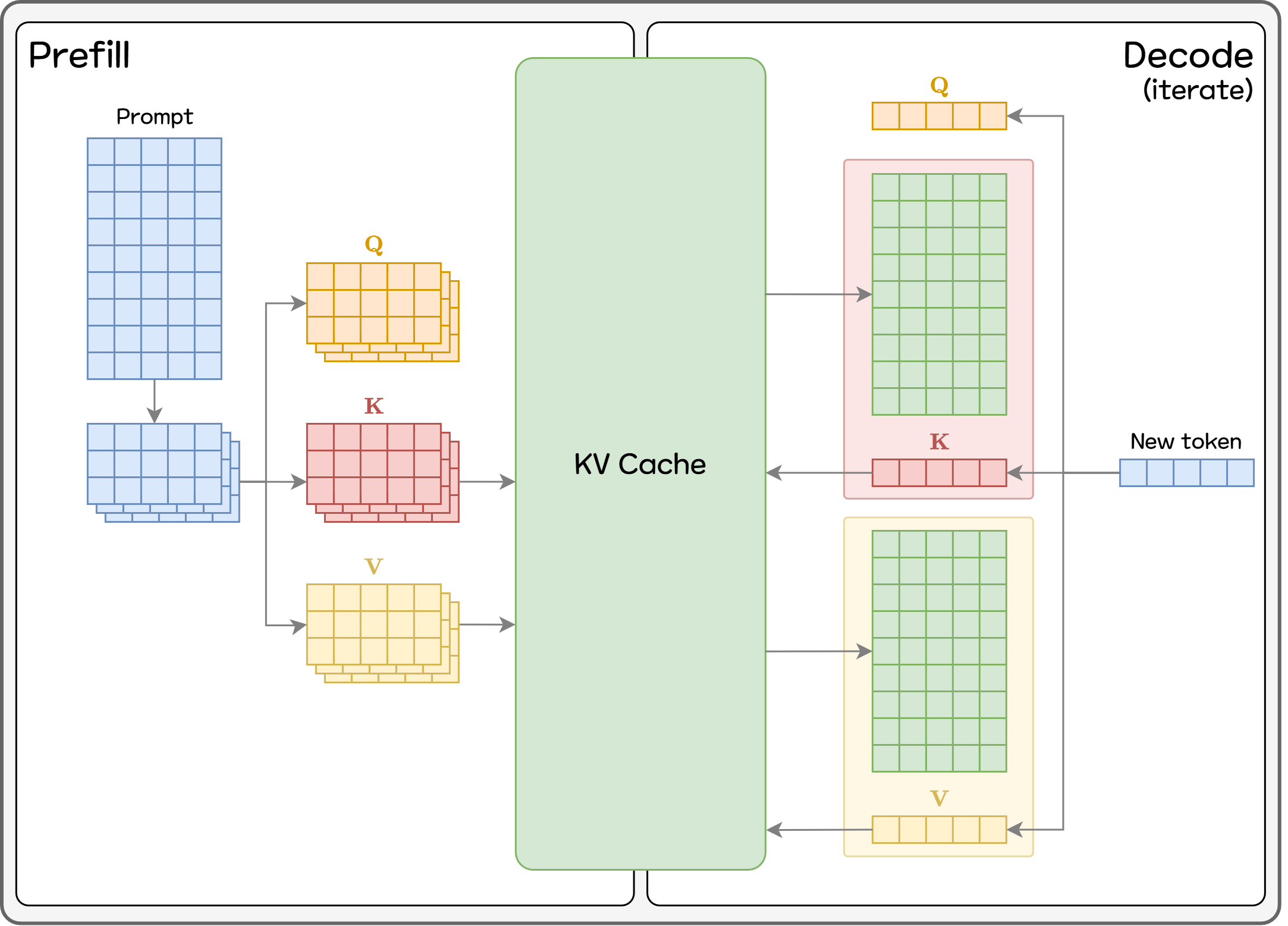

3.1. KV Cache

If the model were to recalculate all previous tokens every time, inference would inevitably become slow. Therefore, most LLM serving engines use KV Cache, which stores the Key/Value vectors needed for the next-token computation and reuses them directly. KV Cache is a foundational technique used in virtually all LLM serving systems.

However, KV Cache consumes a large amount of GPU memory, so efficient memory management becomes critical. Three major factors heavily influence GPU memory usage:

- Longer sequences (prompt + generated output)

- Larger model sizes

- More requests included in the batch

All of these cause KV Cache to rapidly expand and dominate GPU memory. Thus, how KV Cache is managed directly affects how many requests a limited GPU can handle, tying closely to service cost and user experience.

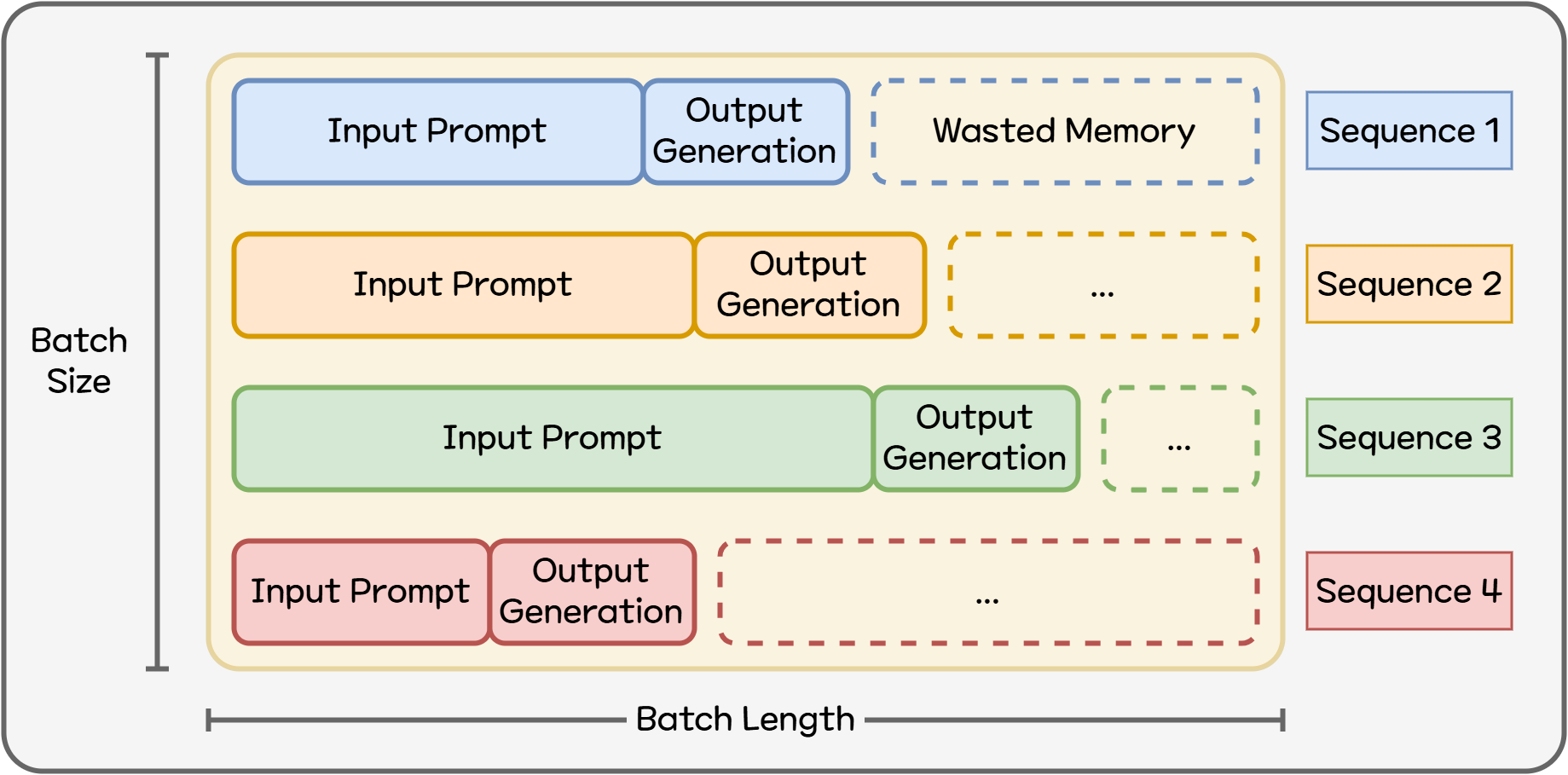

3.2. Paged Attention

As noted above, while KV Cache is essential for serving LLMs, it also becomes the biggest consumer of GPU memory. Traditional KV Cache reserves a large continuous block of GPU memory per request (prompt + response). But each request requires different memory, and a large portion often goes unused. If a sequence (prompt + output) is shorter than the maximum expected length, the excess allocation becomes wasted memory. In real services, where sequence lengths vary widely, choosing a universal optimal allocation is nearly impossible.

Figure 2. Inefficient GPU Memory Usage

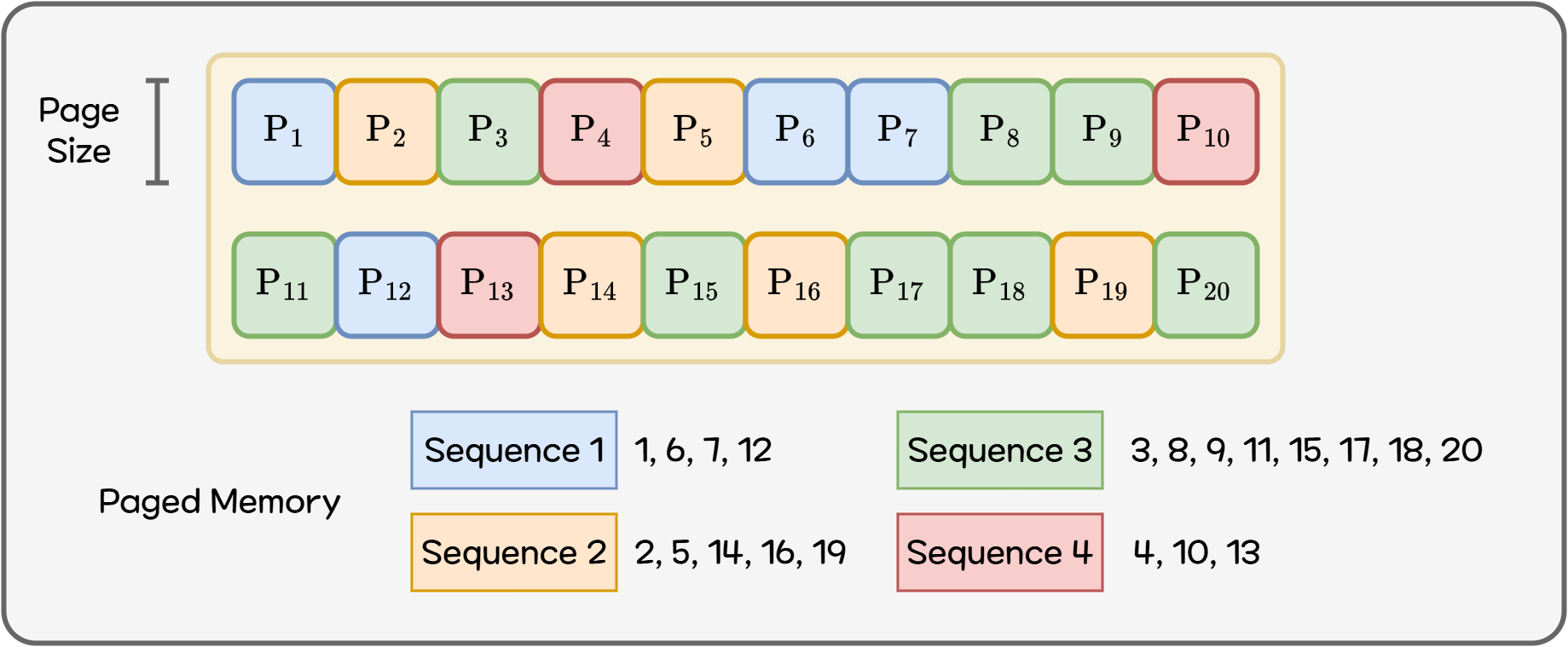

This is where Paged Attention5 — a core innovation introduced by vLLM — comes into play. Instead of assigning memory as a giant contiguous block, it divides KV Cache into small pages and manages them flexibly. If part of a sequence finishes or becomes unnecessary, that page can be reassigned to another sequence.

Figure 3. Paged Memory

This avoids holding memory exclusively for a single sequence, and greatly reduces waste. As a result:

- More requests can be processed concurrently using the same GPU

- Requests with widely varying lengths can all get exactly the memory they need

In EVA, where sequence lengths differ significantly between simple chat and multi-image analysis scenarios — and where we must handle as many camera streams as possible within limited GPU resources — Paged Attention provides a huge advantage.

3.3. Continuous Batching

If Paged Attention improves memory efficiency, Continuous Batching67 maximizes GPU computation efficiency.

Traditional batch inference:

- Collect requests → form a batch → process the entire batch → then move to the next batch But LLM requests differ in completion time (due to different output lengths). Thus, while a slow request continues, faster requests remain stuck waiting, wasting GPU compute capacity.

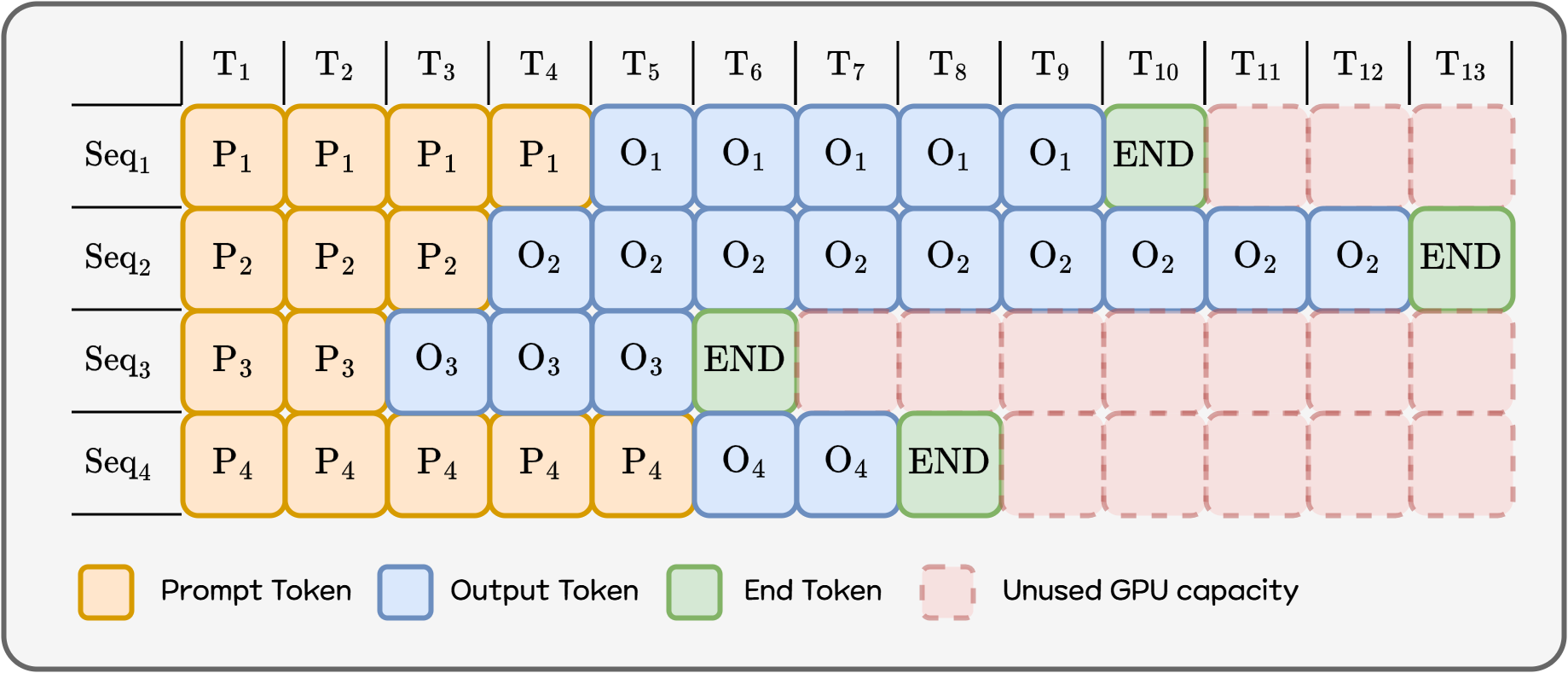

Figure 4. Static Batching

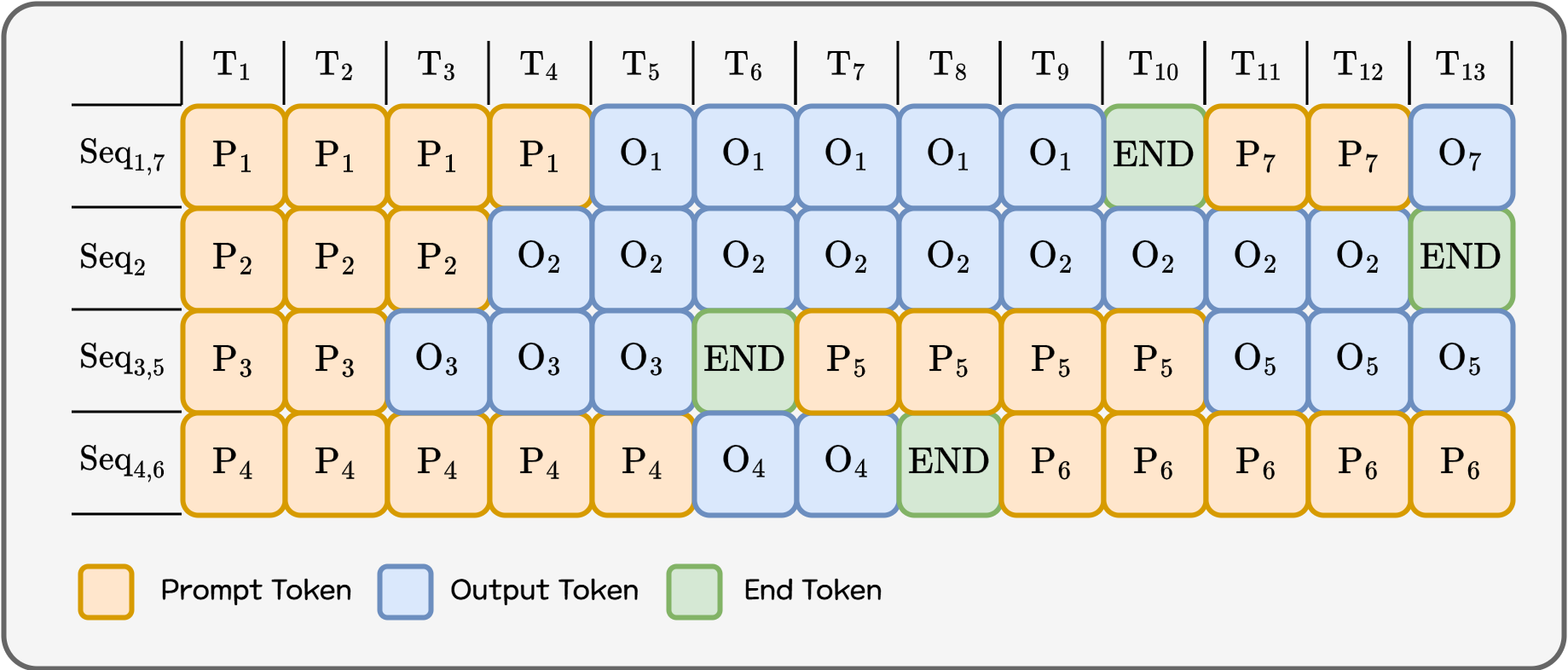

Continuous Batching breaks the process into token-generation iterations. After each iteration:

- Finished requests exit the batch immediately

- Newly arrived requests join the batch instantly

This makes the batch a continuously updating structure rather than a fixed one.

Figure 5. Continuous Batching

This reduces GPU idle time and allows far more requests to be processed within the same timeframe. In particular, for environments with many short requests mixed with long ones, user-perceived latency improves dramatically.

With:

- Paged Attention → efficient memory use, and

- Continuous Batching → maximal compute utilization,

we serve more concurrent requests with lower response time using the same GPU.

Continuous Batching, like Paged Attention, greatly benefits EVA’s need to support many camera streams with varying workloads.

Additional key techniques such as Chunked Prefill[A.1.] and Flash Attention[A.2.] also support performance — but details are covered in the Appendix due to dependency on vLLM’s scheduling and GPU hardware behavior.

4. vLLM Configuration

So far, we have looked at the core technologies used by vLLM to achieve high throughput (Paged Attention, Continuous Batching, Chunked Prefill, Flash Attention). Now, we’d like to share how vLLM is configured in EVA. EVA serves a Qwen3-VL-8B-based VLM using vLLM, and we configured the engine options to fit service requirements. These settings are based on an AWS EC2 server equipped with a single Nvidia L40s GPU. All values should be tuned according to server specifications and real service workloads.

--model Qwen/Qwen3-VL-8B-Instruct-FP8

--tensor-parallel-size 1

--gpu-memory-utilization 0.7

--max-model-len 12K

--kv-cache-dtype fp8

--max-num-batched-tokens 4K

--enable-chunked-prefill

--enable-prefix-caching

-

--model Qwen/Qwen3-VL-8B-Instruct-FP8- We use an 8B FP8 lightweight model from the Qwen3-VL family.

- Larger parameter models exist, but the 8B model provides a better balance of fast response time and throughput for our service goals.

-

--tensor-parallel-size 1- Determines the number of GPUs used for vLLM.

- EVA can serve ~100 cameras on a single GPU server, so we target servers with at least one 40GB GPU.

-

--max-model-len 12K- Maximum context length (input + output tokens) per request.

- EVA sometimes needs to analyze multiple images, so we allocated around 12K.

- Too small → errors on long requests Too large → increases minimum KV Cache memory usage

-

--max-num-batched-tokens 4K- Upper limit of total tokens processed in one iteration.

- This serves as the “token budget” for the Continuous Batching + Chunked Prefill scheduler.

- We increased from the default (~2K) to better support mixed workloads (short chat + multi-image requests).

- Too small → prefill becomes overly fragmented → throughput drops

- Too large → single heavy request dominates an iteration → visible latency increases

- Upper limit of total tokens processed in one iteration.

-

--kv-cache-dtype fp8- The data type for storing KV Cache.

- Using FP8 instead of FP16/BF16 cuts KV memory usage roughly in half.

- EVA prioritizes maximizing concurrent requests, trading slight quality loss for efficiency.

- Verified that response quality remains acceptable for EVA use cases.

- Supported from Nvidia ADA architecture and newer (Ampere supports only 16-bit KV Cache).

-

--gpu-memory-utilization 0.7- Percentage of GPU memory available to vLLM.

- Reduced from the default (0.9) to 0.7

- EVA also runs other ML models on the same GPU, so we reserve memory headroom.

-

--enable-chunked-prefill- Enables Chunked Prefill (Appendix A.1).

- Enabled by default in v1 engine, but we set explicitly for clarity.

- Behavior may differ by version → always verify with release notes.

-

--enable-prefix-caching- Enables Automatic Prefix Caching (APC).

- When multiple requests share the same prefix (e.g., system prompt, scenario description), prefix KV Cache is reused to reduce prefill cost.

- EVA uses fixed system prompts per scenario, making this a highly effective optimization.

5. Conclusion

We discussed how EVA:

- Chose vLLM based on overall service quality, not raw benchmarks

- Tuned GPU usage to maximize cameras per GPU

Summary of EVA’s tuning philosophy:

- Service-appropriate model > Bigger model

- Understand the engine to configure the right values

- Adjust iteratively while monitoring measurable KPIs

There are still open areas to explore:

- Quality vs. throughput trade-offs for FP8 KV Cache

- When/how to adopt speculative decoding or LoRA in EVA scenarios

Service value depends more on how models are applied than on model scale alone. We will continue to evolve model and engine choices for optimal complexity and performance.

We hope this article helps teams with similar challenges get started.

Appendix

A.1. Chunked Prefill

If Continuous Batching is the idea of “splitting and mixing multiple requests at the token level,” then Chunked Prefill89 applies this idea to long prompts. An LLM request is generally divided into two major stages:

- Prefill stage: The entire input prompt is processed once to build the internal state (KV Cache)

- Decode stage: Tokens are generated one-by-one using the accumulated state

Short prompts pose no problem, but as prompts become longer (e.g., a system message + examples + specs totaling thousands to tens of thousands of tokens), a single prefill can monopolize multiple iterations entirely. During this time, decode operations for other requests cannot proceed, and they must wait until the long prompt prefill completes.

Figure 6. Chunked Prefill

The core idea behind Chunked Prefill is simple:

“Split the long prompt into multiple chunks, process only one chunk per iteration, and use the remaining token budget for decode and other requests.”

Let’s think of the maximum number of tokens that can be processed in a single iteration as a sort of “token budget.”

- First, fill the budget as much as possible with currently ongoing decode requests

- If there is still room left, process only part of the long prompt (a prefill chunk)

- Instead of handling the entire long prompt at once, it progresses “bit by bit” across multiple iterations

This way, even if a long prompt is submitted, decode for other requests continues in between rather than being completely blocked. Like in cases involving multiple images, long requests can be processed while short chat requests arriving in the meantime are also handled concurrently. It prevents the entire GPU from being fully occupied by prefill when a scenario prompt is long.

In vLLM’s latest engine (V1), this prompt chunking + continuous batching strategy is built directly into the scheduler, enabling efficient interleaving of long prompts and multiple requests without needing special configuration.

A.2. Flash Attention (IO-aware Attention Kernel)

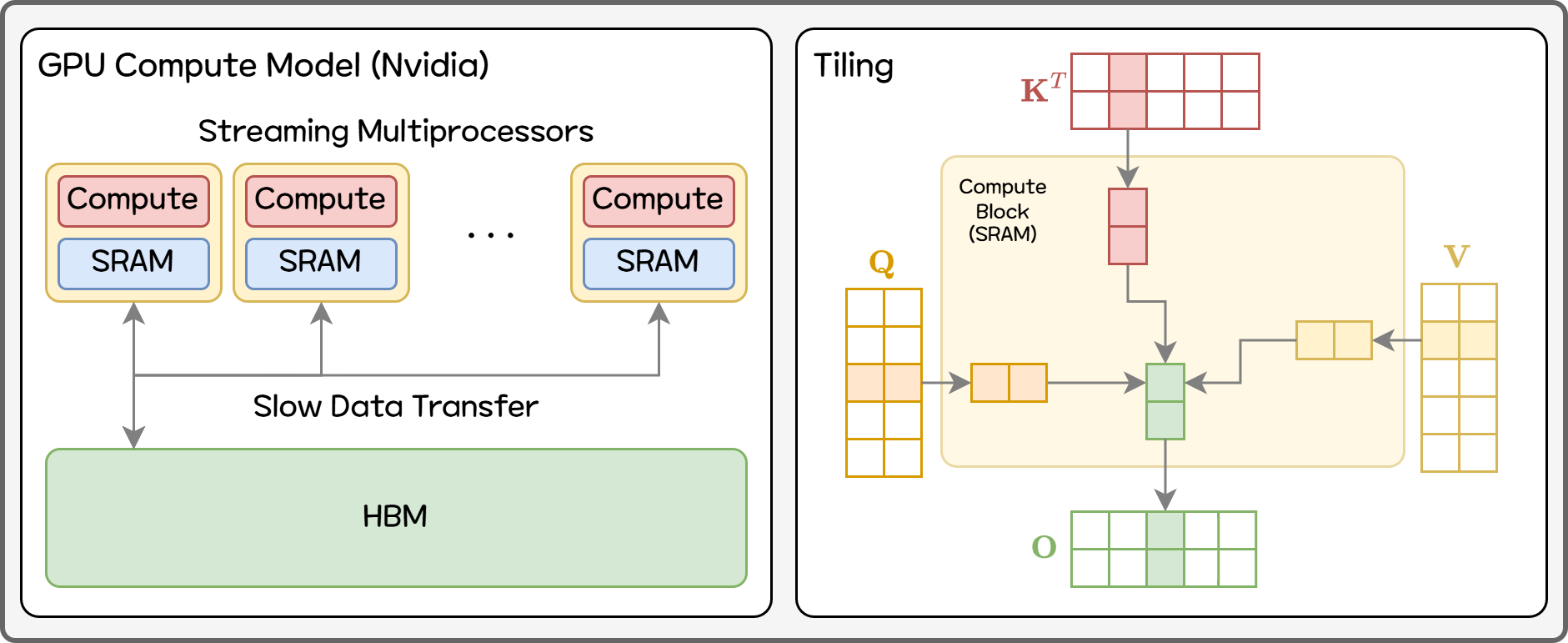

If Paged Attention focuses on “how to manage KV Cache (memory structure)” and Continuous Batching focuses on “how to schedule requests (execution strategy),” then Flash Attention1011 goes one level deeper and changes how the attention operation itself is computed (kernel algorithm). A basic understanding of GPU architecture is required, so we will simplify the explanation. It may not perfectly match the actual hardware behavior.

Figure 7. Compute on GPU

Nvidia GPUs are composed of dozens of Streaming Multiprocessors (SMs), each handling repeated parallel computations. Inside each SM are hundreds of compute units (CUDA cores) and a small on-chip memory (SRAM). For example, an Nvidia A100 has 108 SMs with 192KB of SRAM each — about 20MB total — significantly smaller than what we usually call GPU memory.

By contrast, large data such as model parameters is stored in HBM (High Bandwidth Memory) outside the GPU chip. The GPU fetches only the necessary data from HBM to compute. HBM bandwidth is slower relative to compute speed — causing a major bottleneck.

In large matrix multiplications, if the same data (like a row) is needed repeatedly and must be fetched from HBM each time, IO bottlenecks prevent full utilization of GPU compute power. Thus, GPUs typically divide large data into tiles that fit into SRAM, perform all operations needed on that tile, then write results back to HBM — reducing IO bottlenecks.

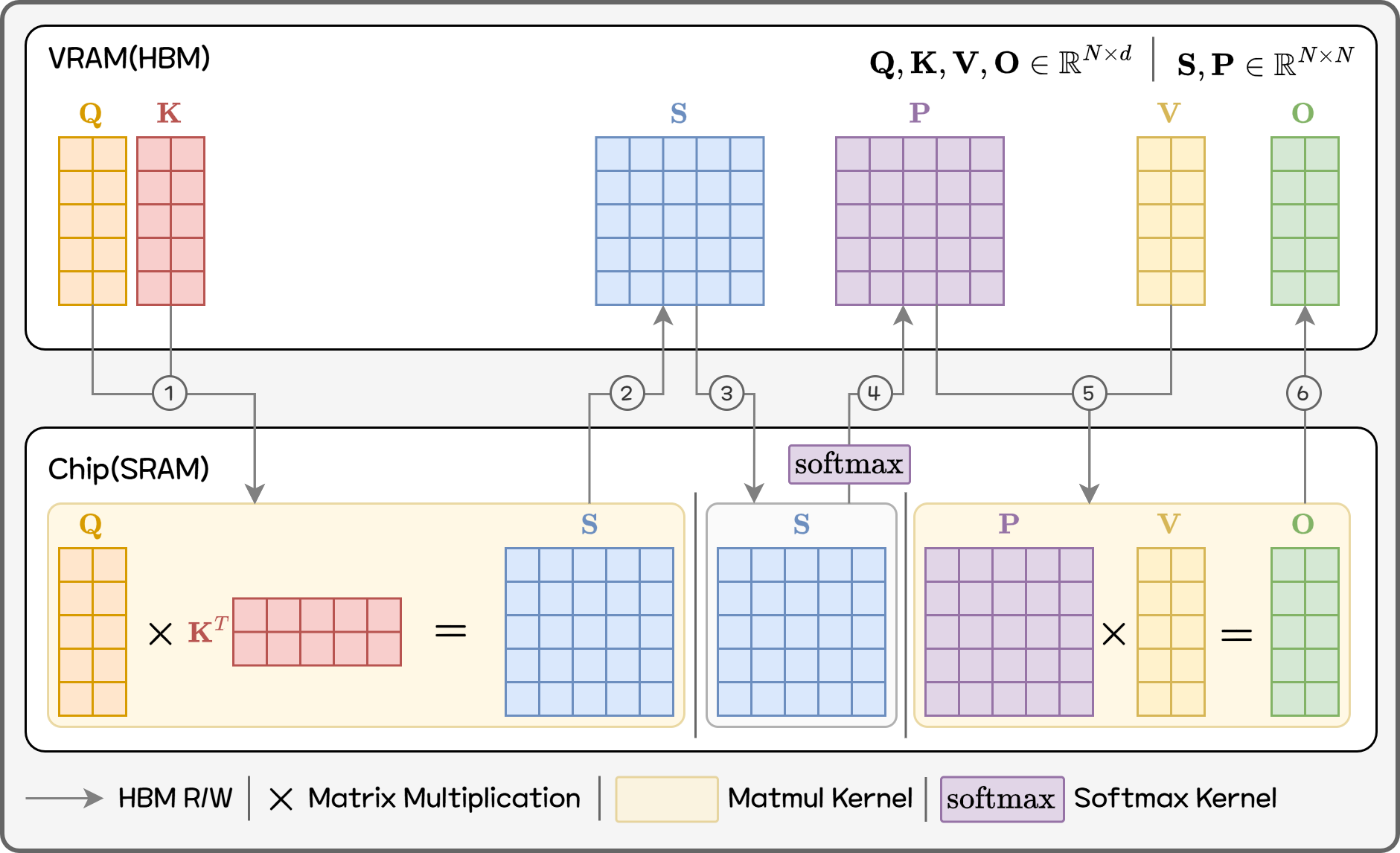

Standard Attention performs these steps:

- Multiply Q and K to create an N×N score matrix S

- Apply softmax to convert S into a normalized probability matrix P

- Multiply P with V to produce the final output

Figure 8. Standard Attention

In theory this is simple, but on GPUs it becomes problematic. Attention on a sequence of length N creates a massive N×N intermediate matrix and requires multiple HBM reads/writes for softmax and matmul. As shown, a single attention operation requires at least 6 HBM read/write steps. Even though compute isn’t the bottleneck, IO becomes one. Memory use and bandwidth both scale as N², worsening with longer sequences.

Traditional implementations separate kernels:

- QKᵀ (GEMM)

- softmax

- PV (GEMM)

Tiling optimizations only happen inside GEMM kernels — tile information is not reused across kernels. Thus, the entire score matrix S must be written to HBM and then read again by softmax. More kernels like mask and dropout exist but are omitted here. This “step-by-step HBM I/O” is the main source of latency for long sequences.

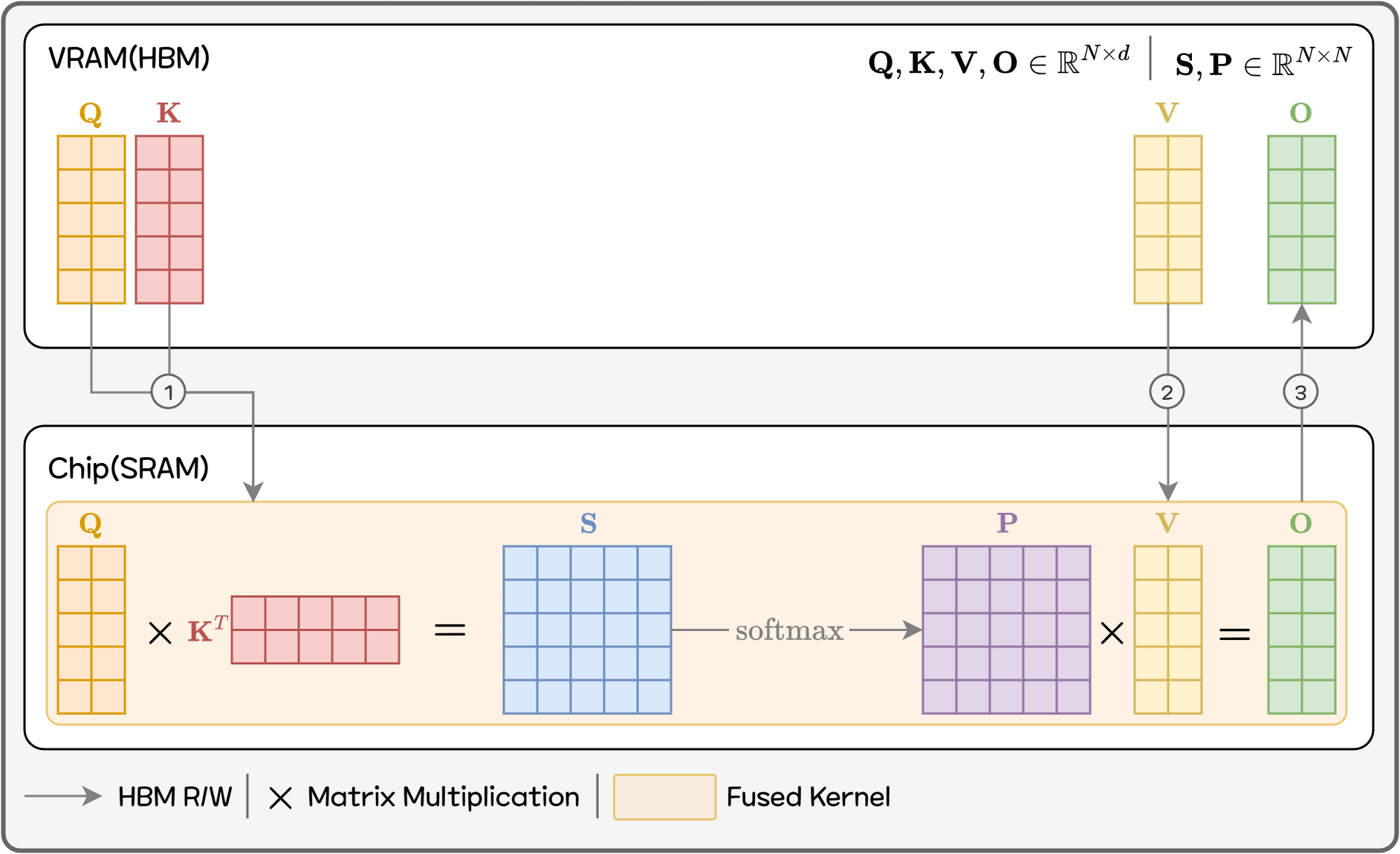

The core idea of Flash Attention:

Do not create the full N×N intermediate matrices at all. Compute only a tile at a time, apply softmax and multiply with V immediately, accumulate results, then discard the tile.

Figure 9. Flash Attention

More concretely, Q, K, and V are divided into blocks that fit into on-chip memory:

- Load one block of Q and one block of K → compute partial scores

- Immediately incorporate results into softmax

- Accumulate into the final output that uses V

- Discard the used tile and move on

Importantly, performing this across all tiles exactly reproduces the same result as standard attention — not an approximation. Only the memory access pattern and computation order change.

This fundamentally changes the attention memory behavior:

| Implementation | Intermediate storage | IO complexity |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Attention | Store full N×N score and probability matrices in HBM | O(N²) |

| Flash Attention | Only Q, K, V, and final output stored persistently | O(N) |

As a result, memory-bound delays are greatly reduced and memory usage is significantly improved.

Footnotes

-

BentoML, "Benchmarking LLM Inference Backends", https://www.bentoml.com/blog/benchmarking-llm-inference-backends ↩

-

SqueezeBits, “vLLM vs TensorRT-LLM #1: An Overall Evaluation.” https://blog.squeezebits.com/vllm-vs-tensorrtllm-1-an-overall-evaluation-30703 ↩

-

Krishna Teja Chitty-Venkata, Siddhisanket Raskar, Bharat Kale, Farah Ferdaus, Aditya Tanikanti, Ken Raffenetti, Valerie Taylor, Murali Emani, and Venkatram Vishwanath, “LLM-Inference-Bench: Inference Benchmarking of Large Language Models on AI Accelerators,” arXiv preprint- arXiv:2411.00136, 2024. https://github.com/argonne-lcf/LLM-Inference-Bench ↩

-

Albert Gu and Tri Dao, “Mamba: Linear-Time sequence Modeling with Selective State Spaces,” arXiv preprint- arXiv:2312.00752, 2023. https://arxiv.org/abs/2312.00752 ↩

-

Woosuk Kwon, Zhuohan Li, Siyuan Zhuang, Ying Sheng, Lianmin Zheng, Cody Hao Yu, Joseph E. Gonzalez, Hao Zhang, and Ion Stoica, “Efficient Memory Management for Large Language Model Serving with PagedAttention,” arXiv preprint- arXiv:2309.06180, 2023. https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.06180 ↩

-

Gyeong-In Yu, Joo Seong Jeong, Geon-Woo Kim, Soojeong Kim, and Byung-Gon Chun, “Orca: A Distributed Serving System for Transformer-Based Generative Models,” Proceedings of the 16th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI ’22), 2022. https://www.usenix.org/conference/osdi22/presentation/yu ↩

-

Yongjun He, Yao Lu, and Gustavo Alonso, “Deferred Continuous Batching in Resource-Efficient Large Language Model Serving,” Proceedings of the 4th Workshop on Machine Learning and Systems (EuroMLSys ’24), 2024. https://doi.org/10.1145/3642970.3655835 ↩

-

Amey Agrawal, Ashish Panwar, Jayashree Mohan, Nipun Kwatra, Bhargav S. Gulavani, Ramachandran Ramjee, “SARATHI: Efficient LLM Inference by Piggybacking Decodes with Chunked Prefills,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.16369, 2023. https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.16369 ↩

-

Amey Agrawal, Nitin Kedia, Ashish Panwar, Jayashree Mohan, Nipun Kwatra, Bhargav S. Gulavani, Alexey Tumanov, Ramachandran Ramjee, “Taming Throughput-Latency Tradeoff in LLM Inference with Sarathi-Serve,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.02310, 2024. https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.02310 ↩

-

Tri Dao, Daniel Y. Fu, Stefano Ermon, Atri Rudra, and Christopher Ré, “FlashAttention: Fast and Memory-Efficient Exact Attention with IO-Awareness,” arXiv preprint- arXiv:2205.14135, 2022. https://arxiv.org/abs/2205.14135 ↩

-

Tri Dao, “FlashAttention-2: Faster Attention with Better Parallelism and Work Partitioning,” arXiv preprint- arXiv:2307.08691, 2023. https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.08691 ↩